Matthew Harris is a serious artist who revels in the ridiculousness of the human condition. His work, most often paintings and sculptures of abstracted representations of the human figure, makes clear that he cares for and is attuned to color theory, art history, contemporary image making, and the psychological realities of contemporary life.

In this exhibition, Harris uses very specific and evocative titles to influence our perception of the predominately abstract work. In his statement he instructs the viewer “not to name the work too early.” For me, he’s already done the naming and that’s fine because these deliberate titles add fascinating complexity to experiencing the work. The paintings and sculptures are luscious and provocative, and the language is as loose, open, expressive, and vivid as the work itself.

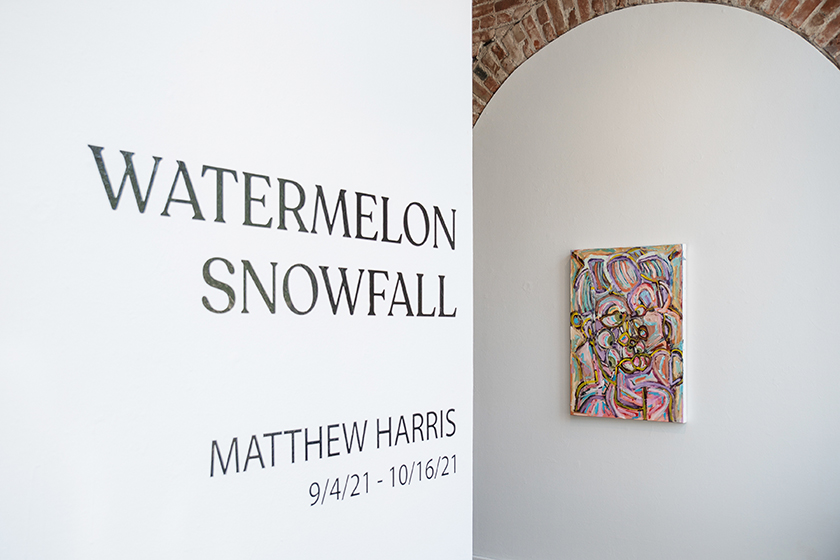

The exhibition is titled “Watermelon Snowfall,” a cartoonish pairing of words that conjures a magical-realist downpour of melons drifting from the sky as plentiful and soft as snowflakes. I imagine we’d all stop at the wonder with child-like amazement, only to be shocked back into the reality of the melons’ weight and potential danger as they

smashed on impact into a gory, sticky mess of gourd guts on the pavement. For a moment we’d be transfixed and dreamy, only to be violently reminded of strange, deadly plagues from our myths, from our history, and from our present lives.

As a new father in a pandemic, Harris has been able to spend amounts of time with his daughter he otherwise might not have, especially in a culture that does not expect much childcare from fathers. As the world shut down, he was immersed in the joy, surprise, curiosity, giggles, farts, bubbles, wabbles, and comedic hand-to-mouth coordination of a baby, all the while 4.7+ million people died. For Harris, combining the solemn with the silly is the stuff of daily life.

As you enter the gallery, a sculpture on a pedestal hints at, and then brushes off, a harm. “It’s Just a Scratch” is a bulbous form covered with curved fins like a pinecone. A supporting structure of thin appendages hold up the blob, and the whole thing is painted and dripped with pearlescent pastels. This figure is more underwater creature, animal, alien, or microscopic virus than Harris’s usual human shapes, but it still reads as organic and alive. The dismissive title suggests that whatever injury the odd being has incurred (or inflicted), maybe it’s not as bad as it appears? The strange seriousness of the form replies, “seems doubtful.”

“Again” is a brightly colored, abstract painting that could be the bust of a figure with many repeating, manic eyes. The painting reminds me of the way Duchamp imaged time and movement with echoing shapes in Nude Descending a Staircase, but the person in Harris’s painting is just a torso whose movement is frantic and ocular, the way I feel after too much coffee and too much compulsive scrolling—panicky and totally out of touch with my body.

Other paintings return me to my body and to new physical sensations. “Sticky Hammock” with its lush, layered pinks and greens and peaches and lavenders is a swirling application of thick gestural paint that immediately brings to mind eating fast-melting popsicles while swaying in a hammock in the middle of summer. Not because that image literally exists in the painting, but because the title hints at it and the painting feels like that feeling. It just takes that linguistic nudge, or playful coercion, paired with Harris’s use of pigment and surface to spill over into a fully immersed imagining. “Spicy Juicy Crunchy,” another highly abstracted painting with joyous color and movement, also alludes to a sensorial experience of consumption. “Lost Ranunculus” celebrates in pigment and gesture to invoke a fecund garden. The vigorous excitement of the painting suggests that Harris surely found the ranunculus. “Help, my Lilac is Melting” is paler, smaller, and flatter, but still expresses floral romping, possibly while micro-dosing. If a figure exists in any of these abstract works, they are being vibrantly (violently?) engulfed by the surrounding corporal delights. Being easily manipulated while desperately, and maybe destructively, seeking joy is very relatable.

In the sculpture “Jellied Limes” a web-like base rises up from the web’s center to approximately 4 feet high like a rope ladder to nowhere, painted in dripping, subtle greens, again with a pearlescent finish. And then there’s the small painting “Lazarus.” A very loose collection of pale color over a dark green ground. Combined with the linguistic direction of the titles, Harris presents a painting and sculpture that conjure a world extended beyond the art object. A psychology and strangeness just adjacent to consciousness. In these two works, even though he hints at escape and new life, Harris is still moored in the disarray of interior, often wrenching human experiences set in the context and complicated realities of this time. Suffering, desire, passion, conflict, doubt, these coils of internal turmoil play out across public life, work, and political structures.

Struggle is also seen in in the iridescent pink and purple sculpture “I Like Your Gusto.” Of the sculptures in the exhibition, this figure is the most human, albeit headless. Or its “head” is stretched and then re-attached to its back. The arch formed by this composition also reads like a large object, rock, or burden. Arm-like and leg-like limbs hold up the figure’s weight and caring load. The sculpture’s surface indicates the artist’s hands working and squeezing the material into shape. And the whole thing is pitched forward as if struggling to make progress and build momentum against a strong wind. The slog looks difficult and exhausting, yet the title, perhaps mockingly, only provides an overly positive, insincere platitude for the figure’s efforts, like an empty corporate axiom, transparently ridiculous as workers die, are laid off, or refuse to return to undervalued, poorly compensated, risky labor.

Harris’s essential earnestness creeps back the more figurative the works become. One figure is particularly more identifiable as a person than any other work in the exhibition and is depicted in a traditional, Western, portrait pose Harris references in much of his work. In this small painting titled “Come With Me,” a black line with white dots cross around and in front of the sitter like snakes or ropes. The painting is tucked in a corner, like a small thing to be discovered, or perhaps the work has something to hide. The title offers an invitation but the inconspicuous location of the work and the encroaching tethers around the figure seem potentially sinister. What might be tempting to a viewer is the recognizable figuration. Especially at a time when uncertainty abounds and we need rest from anxiety, we might just want to know what we’re looking at. The figure in the painting “Adamantine” is also delineated by a web or cage, this time of red and rust- colored lines of paint that outline enough of an abstracted figure to again distinguish that familiar, cannon-established pose. Adamantine is a diamond-like stone regarded for its unyielding hardness and to be adamant is to be obstinate in belief. Both of the figures in these paintings are ridged, their eyes don’t offer any kind of human connection, and although you can see a human form, it’s unknown who specifically these people are. Any kind of certainty the compositions offer is also tethered to an established canon that is rightfully and urgently under scrutiny for its erasure, colonialization, and white supremacy. The paintings have a double-edged quality, both critiquing the intransigence of the familiar while openly acknowledging the canon’s “devil-you-know” allure.

“Powder” also depicts a customary bust but with more ambiguity and thus allows space for further imagined situations. It’s a painting with thick, layered applications of purple and pink. Bold yellow highlights outline a figure that seems to be wearing Micky Mouse ears while strange, turquoise shapes that could be hands gesture toward the figure’s mouth, maybe eating or maybe yawing, maybe consuming or maybe bored. A picture of “let them eat cake” sentiments at the amusement park, it’s a startling association to any kind of mass and unmasked gathering in the midst of a highly communicable airborne disease.

Awe always has an edge of terror. And at times like these, when we are capable of savoring a moment of pure pleasure adjacent to or even interwoven with the inconceivable sorrows of the world, the question presents itself, isn’t this all just so silly? The response is, in life and in this exhibition—yes, and not at all.